BRIAR — Residents of the former City of Briar have been waging an ongoing debate on policing and a struggle against local crime for nearly a half century.

North of Azle and south of Boyd, Briar is a lakeside community of about 7,000 people covering a total space of 21.9 square miles. The locale has not been able to call itself a city since April 2, 1983, when around 80% of voters choose to dismantle the city council and police force.

Since then, Briar residents have lived in an unincorporated status, relying on Tarrant and Wise Counties for most of their services, except for the local fire department which predates the city.

One infamous neighborhood of Briar, formally known as Eagle Acres but colloquially known as “the Briar Patch” is well known for its problems with drugs and crime. At least one Eagle Acres resident is currently the subject of a federal investigation by the Drug Enforcement Agency. Among the prickliest of the Briar Patch’s denizens is Daniel Isaac Reeves. Reeves has had police attention drawn to his and his father’s Alcove Street residence since at least July of 2000. According to Tarrant County District Clerk records, he has been involved in at least 11 criminal cases in Tarrant County, ranging from assault to the manufacturing of an illegal substance.

On June 12, Officer Christian Abrahim of the Lake Worth Police Department, investigators from the DEA Task Force, Tarrant County Sheriff's Office S.W.A.T. Team, Parker County Sheriff's Office and Wise County Sheriff's Office executed a federal search warrant on Reeves’ home. According to an affidavit from LWPD, the bust resulted in officers finding 38 grams of methamphetamine and counterfeit M-30 oxycodone pills containing fentanyl. Prior to the operation, a TCSO Drone Unit observed Reeves discharging a pistol on the property. A Smith & Wesson .38 Special and M&P 5.7 were also recovered during the raid, earning Reeves a charge of unlawful possession of a firearm by a felon, as well. After gaining access to his phone, investigators found text conversations consistent with drug trafficking.

On Friday, Aug. 23, the DEA posted an official notice of property seized for federal forfeiture. Included were a Smith & Wesson 642 Airweight Revolver with ammunition, valued at $202.21, seized by the DEA June 12, and a Smith & Wesson M&P pistol with magazine and ammunition, valued at $192.63.

The public information officer for the DEA’s Dallas Division as well as an agent working on the case declined a request for comment from the Tri-County Reporter, citing the sensitive nature of the ongoing federal investigation.

At press time, according to Tarrant County District Clerk records, Reeves was not in jail, however, he is the subject of an arrest warrant.

According to area residents — two who wish to remain anonymous for their safety — the Reeves property has always been a matchbox full of colorful characters waiting to ignite the Briar Patch. Longtime residents of the area and newcomers alike do not feel safe inviting friends or family over to visit. From frequent trespassing, screaming, fighting, gunshots, dog attacks and trash littering the streets, locals said these cheap lakefront properties come with an unstated price.

“I just got robbed on my boat dock, about $2,000 worth of stuff,” one interviewed individual said. “(I’ve been robbed) what, three, no, four times already … Everyone's been ripped off out there. There's probably not one house (in the area) that has not been ripped off.”

In a previous job going door-to-door in the additions abutting Eagle Mountain Lake, this reporter was told to take caution with requests that solicitors leave for their own safety.

“Oh, it's still dangerous,” one anonymous source said explaining their request to not be identified. “It's dangerous enough you don't spread your name around because if they find out … they'll come back on them. We’ve got to keep low.”

The resident wanted to emphasize that Reeves himself was not typically an issue for him. John Doe was instead largely bothered by the visitors and “customers” Reeves hosted.

“Daniel was not a violent person or anything,” they said. “Some of them people like that, they're violent but I've never felt in danger. I just didn't like all the noise and stuff going on, you know, it just is not good.”

Three area residents spoke of a group of three women who often spent time near or at the Reeves’ household. One of the individuals, Valerie Traglor-Ellis, and the others were said to be a source of conflict for neighbors. They claimed she often trespassed, shouted on the streets at all times of the day and night, fought with those who live in the area and stole from their properties.

The Azle woman was also arrested in June after hijacking a mortuary van from John Peter Smith Hospital for a supposed joyride around Fort Worth. The van, and the corpse it contained, were recovered in front of the Fort Worth Zoo later that night.

Residents were hopeful that with the raid some change might come to that corner of Briar. To their dismay, Reeves was quickly bailed out of jail by his father and within a matter of days another warrant was issued for his arrest for another alleged drug possession incident. At the time of publication, law enforcement agencies are still searching for Reeves. At least two interviewed individuals allege they have seen Reeves back at his father’s house on Alcove Street since the warrant was issued. Reeves’s modus operandi, according to one J. Doe, includes making regular trips in a motorized scooter around the neighborhood, as far south as Goodman Lane, to make drug deals.

Even when law enforcement apprehends Reeves again, the resident fears that it will ultimately not address the extent of the community’s problem. They continue to see drug deals go down in the area regularly. A boat ramp near Reeves’ home has served as a frequent spot for these transactions. The individual also claims to have witnessed known drug dealers and associates of Reeves remove suspected narcotics from his backyard.

“I'm scared we're just going to be like, ‘OK, well, we got rid of one guy, on to the next neighborhood,’ or something like that,” Doe said. “We got one guy in the neighborhood, there's 15 other Valeries I need (police) to take care of.”

Driving through Eagle Acres, dilapidated houses and overgrown yards strewn with trash are a common sight. More recent newcomers, with nicer houses, high fences and extensive home surveillance, have also joined the fray for the destination’s cheap prices and available land.

One such resident, Mike Henry, is a retired Air Force veteran who moved into the neighborhood several years ago with his wife. Henry described one incident in which a shooting took place on the dock behind Reeves’ property.

“We thought it was a really nice, quiet little community and then there’s crackheads running around out here,” Henry said. “There's a couple of characters that are regulars, I guess you would put it and, you know, run up and down the streets out of their mind on drugs. I have my grandchildren here quite often and we were out there one evening. They were getting kind of loud close to the door. This was probably around October, I guess, last year and there were some motorcycles over (in Reeves’ yard). People start pushing, then shoving and then the guns come out.”

Through his experiences speaking with neighbors, Henry has come to understand that his community and adjacent streets are a hotbed for drug activity.

In explaining why the Briar Patch is so prone to crime, one Doe referred to the “Broken Windows Theory.” The theory was proposed in 1982 by social scientists James Q. Wilson and George Kelling and posits that if one window in a building is left broken, the rest will eventually be smashed out as well. By not addressing infrastructural problems early, the resident said safety and quality of life have been on a downward spiral.

Two anonymous sources spoke of one property on Base Street that built up walls to conceal a “junkyard.” The property, they said, was so overloaded with trash and scrap that its owners had to park in the street due to a lack of space.

“It's the most insane thing you've ever seen,” one said. “It's just like, because it's so trashy, nobody gives a (expletive). There's not a city here. Nobody comes by and picks up this stuff, they'll leave out there for years. We've had this other problem in this area where people drive by with living room suites and just kick them out at the back end of the street. It happens all the time. It’s like this because neglect just feeds on neglect and neglect.”

Another source also described a different nearby home that was a constant source of smell and rats with a trash pile that has been building and festering for more than a decade.

“It looks like a third world country,” Henry also said of the area in general. “(There’s) just trash everywhere, (junk) piled up everywhere and I know, you know, it's unincorporated. They're not going to send anybody out here and start giving them tickets, and they probably wouldn't do anything but tear the tickets up. So, I don't really know what you could do there. There are some people that are buying some of these properties and starting to build on them. I think that will help, hopefully, but then you never know. You know what those people are going to be like … I really wish it would get cleaned up. I think it's overdue.”

The trash problem was not the only thing being ignored, according to locals. Henry described one instance where a woman was walking down the street and in duress when she was passed by a Tarrant County Sherriff’s vehicle that did not stop to check on her and how that deeply bothered another neighbor. Another Doe described similarly not being pleased with the outcome when police are called.

“Most of the time they'll just tell you, ‘we can't do anything until something happens,’” they said. “Yeah, that's kind of the approach that police have period. It really sucks. Their response time is not usually real bad if they come. That's just the thing, if they come. Then usually if they do, they've dealt with these people for quite some time, so they usually just run them off and they'll be right back in just a few hours. They're not really scaring anybody, if you know what I mean.”

No longer having a dedicated city police force, Briar does not receive the same consistent police coverage as nearby cities like Azle. Doe has reached out to various law enforcement agencies, county commissioners and other officials about these problems for years, with, from his point of view, little effect.

“We got to start getting some funding,” Doe said. “There needs to be some police presence up in here. I'm not naive to think that this is going to get rid of the drug problem. The drug war has been going on for a long time, and they're not winning it. I get it. You're not going to get rid of it, but you could at least put a check on what's going on out of here. The cops come down and go, ‘oh yeah, we're aware of what's going on in the neighborhood.’ I've had one deputy go, ‘well, you do live in the ghetto.’ Well, it's the (expletive) ghetto because you allow it to be the ghetto, right?”

When asked to comment on the state of crime in unincorporated Tarrant County or provide facts or figures on the area, the Tarrant County Sherriff’s Office did not respond; however, the limited data that exists publicly reinforces the claim that Eagle Acres has more than its fair share of issues.

There are six individuals on the sex offender registry living in Eagle Acres alone, five involved in crimes with minors. Eagle Acres covers an area of approximately 0.088 square miles. Texas only has about one sex offender per one-third of every square mile on average. The Tarrant County side of Azle has about 29 sex offenders in about 8.10 square miles, averaging out to about 3.5 sex offenders per square mile. If scaled up, Eagle Acres would have about 68.18 sex offenders per square mile.

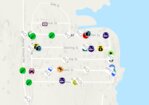

An ArcGIS Tarrant County Crime Map which has not been updated since May 2023, shows that the little neighborhood of Eagle Acres is overrepresented compared to many nearby locales. From Sept. 12, 2021 to May 12, 2023, the map shows about 40 calls for service for a wide range of crimes in the Eagle Acres additions. The City of Pelican Bay shows about 56 calls for service in that same period despite covering a much larger area of about 1.25 square miles. This would put Eagle Acres at about 454.5 calls per service per square mile and Pelican Bay at 44.8 calls for service per square mile, for comparison.

In addition to problems on their side of the lake, one resident also worries about stray bullets coming from megachurch pastor Kenneth Copeland’s compound on Eagle Mountain’s eastern shores. From the sounds they hear, the individual assumes that people on Copeland’s property must be using “AK 47s” for recreational shooting or target practice. When viewing the properties on Google Earth, Eagle Acres appears to be directly adjacent to the northern portion of Copeland’s 24-acre tax exempt lakefront tract containing his $7 million mansion, private airport and Kenneth Copeland Ministries headquarters.

Despite the mountains that need moving to get the neighborhood on the right track, at least one resident says there has been an improvement after Reeves’ arrest. After others made calls to action to the Precinct 4 Commissioner Manny Ramirez and other public officials, some of the trash issues are finally being addressed as well.

“It’s just like a completely different neighborhood now and I know there's still those meth heads out there, but they don't bother me,” one resident said. “They don't bother me; I don't bother them. Drugs is always going to be around but if you start acting a fool and screaming and yelling and shooting guns and stuff, you know. Now there's not as much gunfire as there used to be.”

Public nuisance warnings have recently been issued to multiple houses in the area for the overflow of garbage. After 30 days, if cited houses have not cleaned up their properties they will start receiving fines. One homeowner, Benny Harris, took to Facebook to voice his concern about having received the notice. According to Harris, who has lived in the area for 63 years, he will be unable to complete the work necessary on his property within the month allotted and he thinks law enforcement resources could be better utilized for other purposes. Harris did not respond to a request for comment by the Tri-County Reporter.

“We had been told for years that there weren't rules or statutes that could be enforced down here,” an anonymous resident said. “Apparently, Manny Ramirez has a different mindset on these issues. So far, I'm impressed with the response from his office.”

Echoes from the past

By most metrics, 1983 was not a good year for the City of Briar. Illegally appointed police marshal and mayor, Ray Riley, resigned from his posts. The next mayor, Billy Edwards, also resigned. A highly controversial city council decision deannexed the Wise and Parker County portions of the city. Eventually, its residents voted to abolish Briar, less than 12 years after it was initially incorporated.

Over the year before the disincorporation vote, Briar residents filled The Azle News Advertiser with letters to the editor describing their positions either for or against the dissolution of Briar’s governing bodies. Those in favor of disincorporation would cite such reasons as lower taxes, corruption and an over-budget police force. The Briar Police Department consisted of nine officers and two cars. Some residents doubted the qualifications of some of Briar’s officers and criticized its size.

“What have we to look forward to?” A.T. and Mary Harris asked in a letter to the editor. “Perhaps a total police city? You have not repaired one single street: not one playground or park has been built for the families of Briar to use and enjoy — just a continual build-up of law enforcement.”

For several years, the city had an appointed police marshal in charge of the BPD. At the time, this violated laws dictating what sort of official could oversee the city police force based on its municipality type. Briar residents brought the issue to city council meetings only to reportedly be snubbed by Mayor Pro Tem Sparky Pearson and council members. A new group calling itself the Concerned Citizens of Briar, led by resident Sherry Davis, would then involve lawyer Weir Wilson to sue the city. Wilson successfully argued their case in court. To correct the issue, Chapters 1 through 10 of Vernon's Texas Civil Statutes were adopted by Briar City Council which, among other things, created a proper elected sheriff’s position.

Those against disincorporation cited the increased time it would take for county law enforcement to reach crime scenes and the possibility that disincorporation would lead to decreased funding to the Briar Volunteer Fire Department and other critical resources.

“I personally know of a person with a place of business in Briar that has called Tarrant County on three separate occasions,” Briar resident and city council candidate Paula Barrett said in a 1983 letter to the editor. “On one, they never showed up. In the other two instances, there was a thief right there in the business but by the time Tarrant County Police got there the thief was gone. But how long would it take a Briar policeman to come to your aid? Since Chief Asikis (then Sheriff Greg Asikis) has been on our force, he has solved one burglary and is wrapping up a second case now. He’s also coming along very well with a local felony. He knows Briar and the people of Briar because he is our policeman.”

Not long after, Asikis announced his resignation in the paper for reasons related to the vote for disincorporation and a job offer elsewhere.

The year before, September 1982, Riley and investigator Ray Perry busted an amphetamine lab stated to be capable of bringing in $134,400 per week after the Briar Police Department responded to a reported domestic disturbance where a man fired shots into the air. A 1982 article in The Azle News states that Riley and Perry recovered “enough equipment to supply two good-sized amphetamine labs” along with stolen goods, a carbine, a bandolier of 30 caliber machine gun bullets and 18 knives of assorted sizes.

During a Feb. 1, 1983, Briar City Council meeting, the council voted to deannex most of the Wise and Parker County portions of the city. This left Briar about one-third its original size with about half its original population of 1,800. Pearson argued that the concerns of Briar residents in Wise County, who had been plagued by deteriorating roads, could be more easily addressed if they were instead the direct responsibility of the county and that most of the citizens who were in favor of disincorporation lived in Wise County.

Only two of Briar’s six-person council voted. Councilmembers Maralana Buckley and Joan Cornelius voted in favor of deannexation while councilmember William Gay abstained from voting after asking to table the issue, having only learned about the ordinance minutes prior to the meeting. Councilman Buck Cannon was absent. Pearson did not vote, and the remaining seat remained vacant after the resignation of Mayor Billy Edwards four months prior. Pearson took over the duties after the mayor’s resignation but was said to have refused to occupy the vacant mayor’s seat, preventing an election for a new mayor.

Today, Edwards resides at an eldercare facility in Springtown. He declined to meet with the Tri-County Reporter for an interview, with the center’s activities director relaying that “there are things he’d rather not discuss about that time he was mayor.”

According to the former editor for the Azle News Advertiser, Stephen Bell, the entire discussion of deannexation, from its introduction to its passage into law, took place over the course of half an hour.

Concerned Citizens of Briar interpreted the act as a power play by Pearson to disqualify many of the signatures they had collected in favor of disincorporation. In order to get disincorporation on the April ballot, the group needed at least 400 signatures from Briar residents. They had gathered 643 names, 296 of which were from Wise County Briarites, 258 from Tarrant, and 89 from Parker. Briar’s city council hall erupted into tumult after the decision was made, Bell wrote.

Pearson later argued in the newspaper that Concerned Citizens of Briar “intentionally deceived and misinterpreted the facts in order to gain signatures.”

The validity of Wise and Parker County signatures was affirmed by federal courts and residents in these parts of Briar were granted the right to vote in the city’s April 2 election on the disincorporation issue, where they handily voted to abolish the city. Voters also rejected reincorporation in a subsequent election Nov. 8, 1983.

Despite disincorporation and the four decades since, the debate on policing continues to rage on in the former city today.